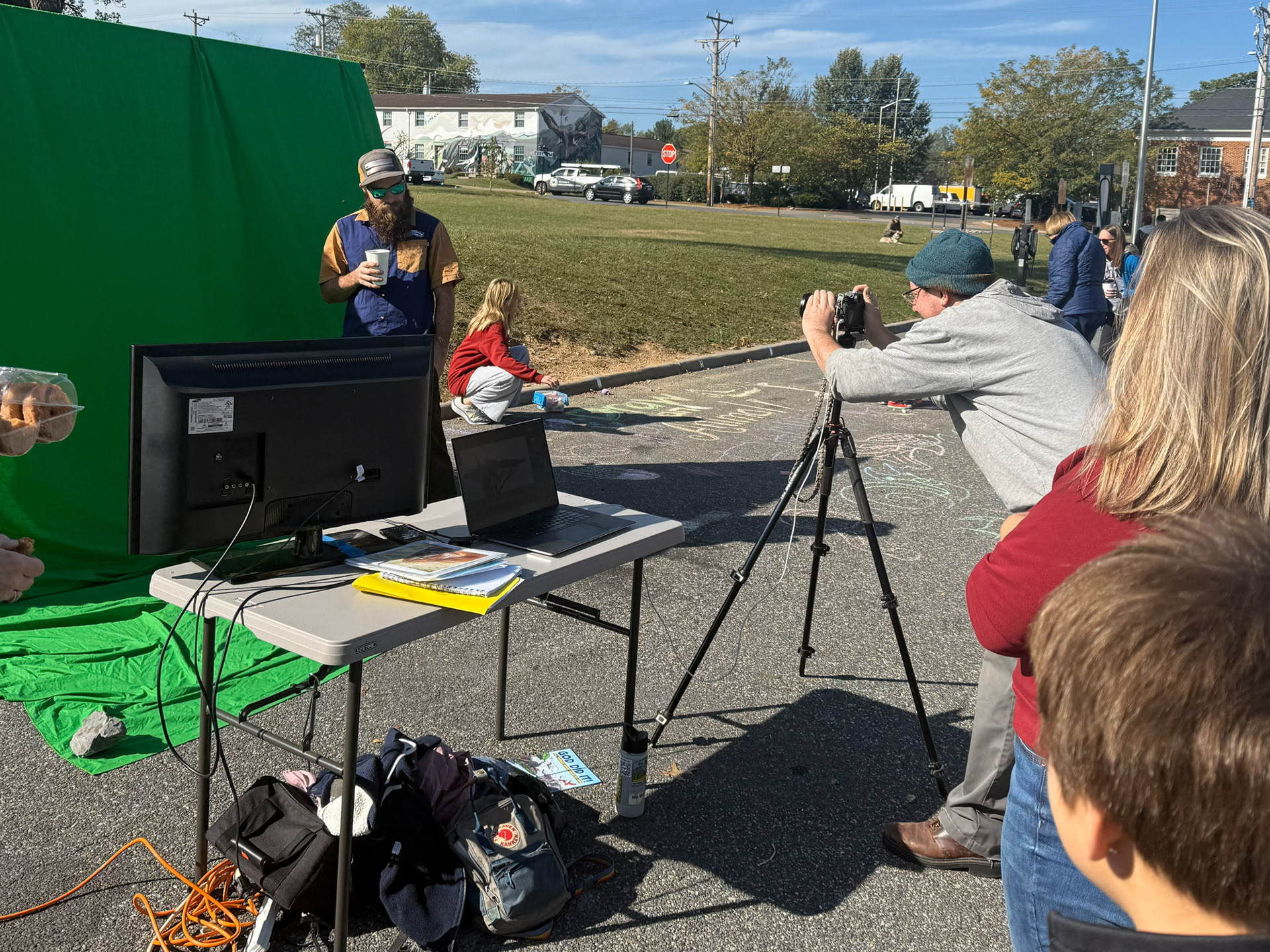

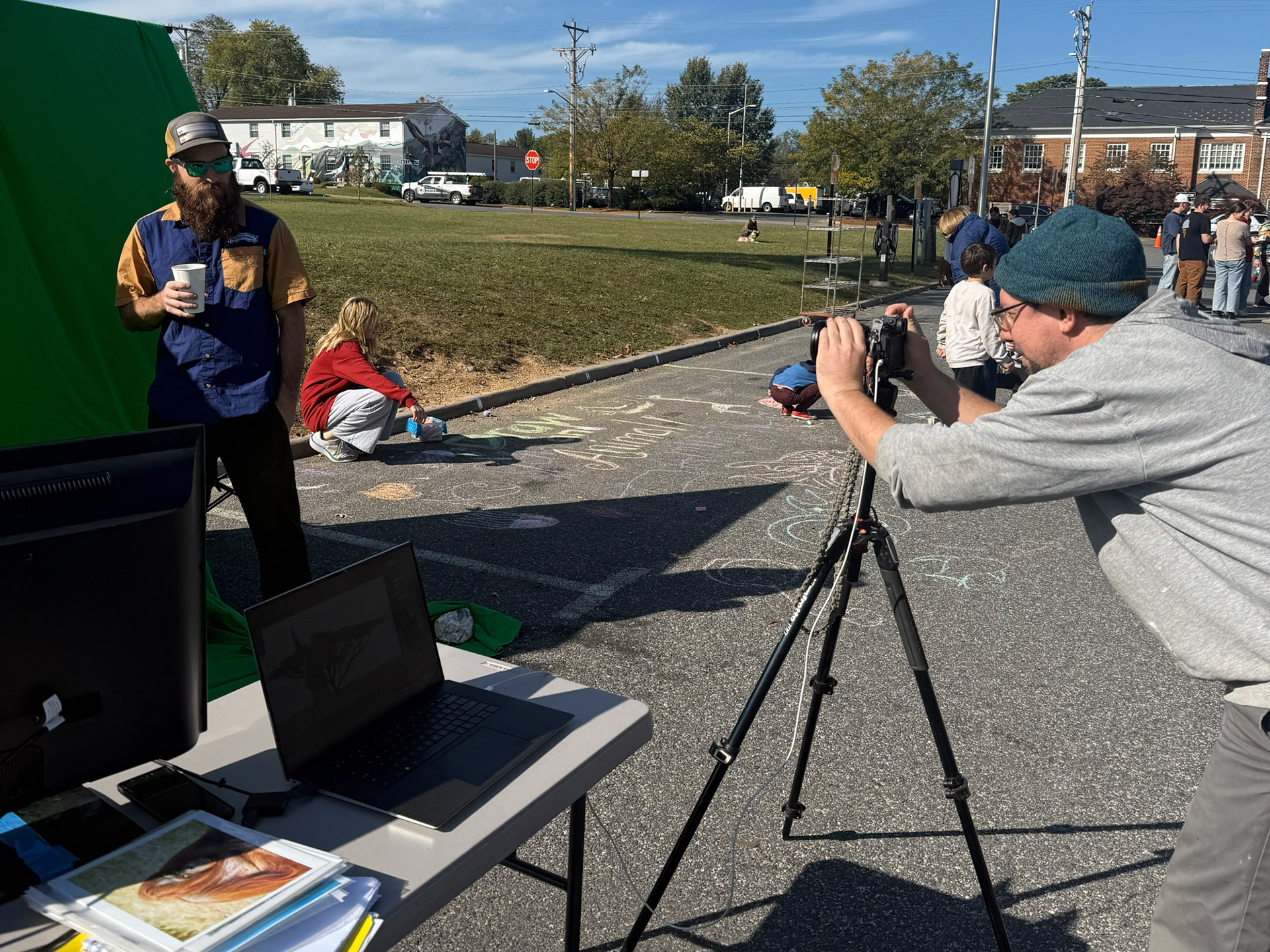

"Take a picture with nature, it'll last longer."

Public photo engagement activity, 2025. In collaboration with Renée Calway .

Harrisonburg, VA

Take a Picture with Nature, It’ll Last Longer:

The Performance of Preservation

In this interactive performance piece, Take a Picture with Nature, It’ll Last Longer, the cheerful atmosphere of a local farmers' market is disrupted by a sleek, professional green-screen studio. The setup is inviting—a photo studio set up, green screen, and a binder of choices—but the conceptual core is a biting critique of how we consume "nature" as it disappears.

"Take a Picture with Nature, It’ll Last Longer" is a play on a colloquialism usually reserved for staring, but here it takes on a literal, tragic weight. By offering participants a "last chance" to stand alongside critically endangered ecosystems—glaciers, coral reefs, and rain forests—the project highlights the shift from experiencing the natural world to archiving it as a digital surrogate.

The work draws a direct line between contemporary environmental tourism and the colonial history of photography. Just as 19th-century figures like Buffalo Bill "staged" the American West—posing with Indigenous people in exaggerated costumes to satisfy a white narrative of the "vanishing exotic"—these participants pose with "vanishing nature."

The project suggests that our modern desire to photograph an endangered reef is not so different from the colonial urge to "capture" a culture before it was suppressed. In both instances, the camera is a tool of value transfer; it takes the essence of the subject and converts it into a trophy for the viewer. The participant becomes the protagonist in a romanticized narrative, while the "nature" in the background is reduced to a static, decorative prop.

One of the most striking aspects of the performance is the cognitive dissonance of the participants. Despite being told upfront and repeatedly that the images they are choosing represent ecosystems in a state of collapse or extinction, the people in the photos are often smiling, laughing, and enjoying the professional "studio" experience.

This reaction exposes a profound disconnect. The "Nature" being engaged with is no longer a living, breathing entity, but a "brand." The participant isn't mourning the glacier; they are celebrating the professional quality of their own image. The work effectively demonstrates how the aestheticization of catastrophe allows us to witness the end of the world through a lens of personal vanity and entertainment.

The project also functions as a data-collection exercise, revealing the human bias toward "charismatic" landscapes. Participants were recorded to consistently choose lush, beautiful vistas over "boring" deserts or "unappealing" insects.

This preference reveals a hard truth about conservation: we are more likely to mourn what we find beautiful. By recording these choices, the exercise exposes the superficiality of our environmental grief. If an insect is critical to an ecosystem but "ugly" in a photo, it is left out of the frame. This "curated nature" reinforces the idea that the environment only has value insofar as it provides a pleasing backdrop for human activity.

When the participant receives their emailed photo, they possess a high-resolution lie. They are standing in a world that is already gone, or soon will be, rendered in vibrant pixels that mask the "destructive states" mentioned in the project's binder.

"Take a Picture with Nature, It’ll Last Longer" is a haunting reflection on the absurdity of the Anthropocene. It suggests that as we continue to destroy the biological world, we are frantically replacing it with a digital one—one where we can keep smiling in front of the green screen, even as the forest behind us is deleted in real-time.